In the fight against climate change, there is a wide gap between what people believe and what they do. Millions acknowledge that climate change is a serious threat, yet their everyday behaviors do not always reflect that concern. This phenomenon—sometimes called the intention–action gap—means that although someone may trust climate science and theoretically support solutions, they may still avoid taking concrete actions, especially when such actions require personal effort or sacrifice.

For example, many express alarm about global warming but choose to drive short distances instead of walking, or they postpone lifestyle changes that could reduce emissions. Faced with this reality, the question becomes inevitable

how can we motivate people to act even when it demands personal effort?

A new study published in Communications Psychology and led by Jo Cutler and Luis Sebastian Contreras-Huerta (2025) addressed this question by testing eleven psychological interventions designed to promote climate action. The results reveal which messages can turn passive concern into active effort for the planet.

A global experiment to measure climate motivation

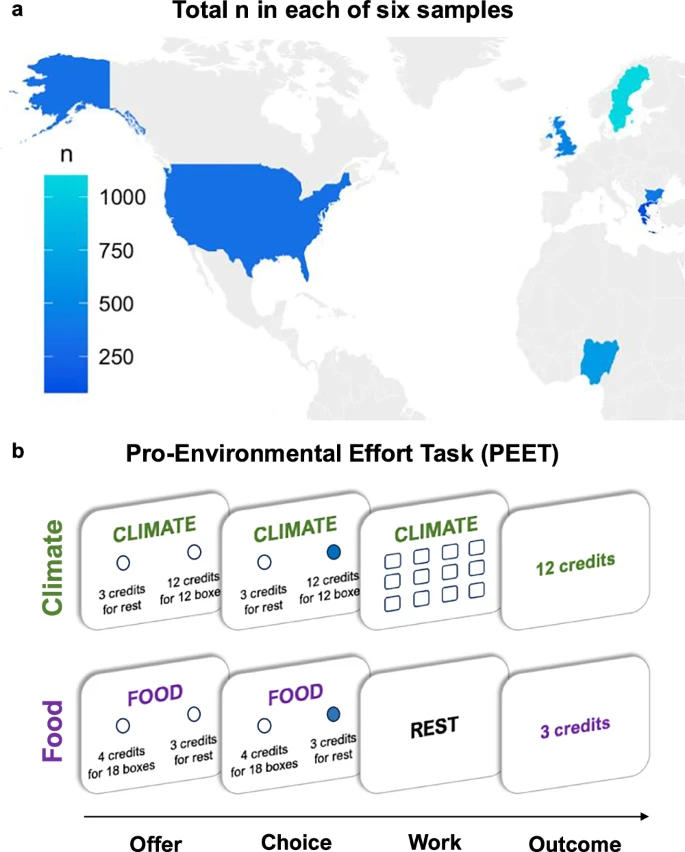

The study’s central test, the Pro-Environmental Effort Task (PEET), measured how willing participants were to perform real physical effort for the benefit of the environment. More than 3,000 volunteers from six countries (Europe, Africa, and North America) completed the task online.

In the PEET, they repeatedly chose between

- an “easy” option (resting, requiring no effort) that generated a small donation and

- a “hard” option (performing physical effort) that generated a larger donation for a charitable cause.

The novelty was that the beneficiary causes alternated: in half of the decisions, the donation went to an environmental project (reducing CO₂ emissions), and in the other half, to a non-environmental humanitarian cause (relieving hunger). This allowed researchers to measure whether people are less willing to exert effort for climate causes than for an immediate good.

In the control group (no psychological intervention), this bias was clear: participants were significantly more inclined to help the hunger cause than the climate cause, even though the required effort was identical.

In other words, although both altruistic acts involved the same physical cost, climate action was less motivating than helping a direct humanitarian cause. The study examined whether brief interventions could close—or even reverse—this motivational gap.

Eleven psychological interventions put to the test

The research tested 11 different psychological interventions, designed by experts, to increase pro-environmental motivation. Each participant was randomly assigned to one of these motivational “nudges” (or to a neutral text in the control group) before completing the task. The interventions spanned various theoretical approaches, targeting known mental barriers.

Some emphasized social influence: one message framed climate action as a collective effort (Collaborative Norms: “we’re all in this together”); another showed that more and more people are taking climate action (Dynamic Social Norms); and another corrected the belief that “nobody cares” by revealing that most of the public does see climate change as an emergency (Pluralistic Ignorance).

Other strategies reframed the issue: one portrayed climate change as a direct threat to the national way of life, urging ecological action as a patriotic duty (Challenging System Justification); another appealed to traditional moral values of loyalty and authority to support climate measures (Binding Moral Foundations). Psychological distance was reduced by showing immediate local impacts so that the risk felt “here and now” (Psychological Distance).

Temporal perspective was also explored: some participants visualized their “future self” holding them accountable decades from now (Future Self-Continuity), and others wrote a letter to a child of the next generation explaining how they are protecting the planet (Intergenerational Responsibility).

Informational interventions included highlighting that 99% of scientists agree on the reality of global warming (Scientific Consensus) and showing successful climate protests and policies to inspire collective efficacy (Effective Collective Action). Finally, one condition exposed volunteers to stark images of natural disasters to evoke fear and indignation (Negative Emotion). None of these stimuli mentioned the effort task itself; their goal was to influence mental state and general climate motivation before the decisions.

Results: closing the gap with well-crafted messages

After the task, researchers compared how often each group chose to “work” for the climate. The results were mixed: only some interventions significantly increased effort for the environmental cause.

As expected, the control group showed a clear preference for the hunger cause, but three interventions managed to eliminate this disadvantage for climate causes. Participants who received the Psychological Distance, System Justification, or Negative Emotion messages were just as willing to exert effort for the climate as for the humanitarian cause. In other words, these groups no longer preferred helping hunger over helping the planet. Statistically, the odds of choosing climate-related effort increased significantly, closing the initial gap (~13% more help for hunger in the control group).

Most of the other eight interventions did not produce clear behavioral changes. This does not mean they are useless; rather, under the experiment’s conditions, their effects were modest compared with natural variability. It is revealing that the interventions that either shortened psychological distance or challenged system inertia were the most effective. Making the problem feel close and appealing to pride in one’s community pushed more people to “roll up their sleeves” for the climate, just as—though more controversially—did the negative emotional content. After reading about local climate impacts or patriotic duty to protect the nation, participants viewed climate action as just as worthwhile as the humanitarian cause.

Motivational mechanisms: effort discounting (K)

To explain why certain messages worked, the researchers modeled decision-making by assuming that donations “lose value” as the required effort increases. This devaluation is quantified by the parameter K (one for climate, another for hunger):

- a high K indicates strong effort aversion

- a low K reflects greater tolerance and therefore more motivation.

In the control group, K_climate was higher than K_hunger, revealing a baseline motivational gap: without intervention, people need more incentive to act for the climate than for an equivalent humanitarian cause.

The key finding is that four interventions—Psychological Distance, System Justification, Pluralistic Ignorance andFuture Self-Continuity—reduced K_climate until it matched K_hunger, effectively “lightening” the subjective cost of exerting effort for the planet.

Other interventions (e.g., Scientific Consensus, Collective Action, Moral Foundations, Social Norms) and Negative Emotion did not alter K_climate. The latter is illustrative: although fear-based content increased pro-climate decisions in the moment, it did not change the underlying valuation of the environmental reward; its effect was emotional and transitory—more urgency than stable motivation.

Overall, the successful interventions reduced the psychological “weight” of effort for climate goals—the act of exerting oneself became more tolerable and valuable—without substantially altering decision consistency.

Outlook: from concern to effort

This pioneering study provides concrete evidence that certain psychological interventions can translate climate concern into tangible action. Messages that reduce psychological distance or challenge systemic complacency are particularly powerful in dismantling barriers to inaction.

A hopeful aspect is that many of these strategies do not require large resources, but rather communicative creativity: showing how climate change already affects the community here and now, framing sustainability as part of national pride, or correcting the false belief that we are alone in our concern. Integrated into broader campaigns, these tools can help close the gap between knowing and doing.

Of course, no message alone will solve the climate crisis. These interventions should be viewed as part of a comprehensive effort alongside economic, technological, and structural changes. Even so, the findings highlight that psychology plays a crucial role: it can pave the way for sustainable policies and technologies to be adopted effectively. Offering electric transportation is useless if people are not motivated to leave their cars—but if an intervention turns that gesture into an act of community pride, the sustainable alternative becomes more likely.

In summary: reducing not only carbon emissions but also mental distance can transform passive concern into active effort for the planet. With rigor and creativity, psychological science is offering key insights to help us undertake the challenging—and necessary—journey of saving our shared home.

Reference

Cutler, J., Contreras-Huerta, L. S., Todorova, B., Nitschke, J., Michalaki, K., Koppel, L., Gkinopoulos, T., Vogel, T. A., Lamm, C., Västfjäll, D., Tsakiris, M., Apps, M. A. J., & Lockwood, P. L. (2025). Psychological interventions that decrease psychological distance or challenge system justification increase motivation to exert effort to mitigate climate change. Communications Psychology, 3, 148. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44271-025-00332-4.